31 Oct Agents Provocateurs: Nicki Minaj transformed by Francesco Vezzoli

In the space of two years, hip-hop star Nicki Minaj has made the leap from little known Lil Wayne protégée to object of national obsession, via a number-one album, seven singles simultaneously on the Billboard Hot 100—a first for any artist—and a series of scene-Âstealing cameos, including an epic verse on the Jay-Z and Kanye West track “Monster.†Along the way, she’s established a zany look (all neon, all the time), introduced countless alter egos, and become the first female rapper since Missy Elliott to be cast not as a sidekick but as a bona fide swaggering leading lady.

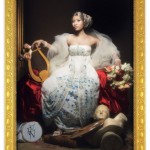

Powerful female figures have always been a draw for the artist Francesco Vezzoli, who has produced a trailer for a mock remake of Gore Vidal’s Caligula featuring Courtney Love and made a fake-fragrance commercial starring Natalie Portman and Michelle Williams. Through film, performance, and images often Âenhanced with embroidery, the 40-year-old Italian links contemporary icons to historic representations of women in art. He transformed Eva Mendes into ÂBernini’s masterpiece The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa for his Prada Foundation installation at this year’s Venice Biennale and, for MOCA’s 30th-anniversary gala in 2009, he reimagined Lady Gaga as a latter-day Ballets Russes star. Now Vezzoli has remade Minaj as an 18th-century courtesan. To discuss the project, he sat down for a lively tête-à -tête with Klaus Biesenbach, director of MoMA PS1, who is organizing a touring retrospective of Vezzoli’s work that will land at the New York venue in 2013.

BIESENBACH: You have a history of collaborating with celebrities. What Âinterested you in working on a project with Nicki Minaj?

VEZZOLI: I wanted to play with the public image of a female hip-hop star. During my entire career, I have always been fascinated by powerful women in history. I have spent a lot of time researching the ways they were represented in art and how their images were used to mold the public imagination—and to convey aesthetic and philosophical ideas about beauty and sexual desire. My main interest has been to link the historical artistic approach to female representation to contemporary icons of the media era.In my most recent works, for example, I transformed Princess ÂCaroline of Hanover into a Garbo-esque Queen Christina, I asked Âactress Eva Mendes to become three symbols of classical sculpture (Venus, Saint ÂTeresa, and Paolina Borghese), and I framed Lady Gaga into a de ÂChirico–inspired robotic extravaganza. For W, I wanted to turn the lovely Nicki Minaj into a powdered 18th-century courtesan.

BIESENBACH: How have you transformed her?

VEZZOLI: In her performances, Minaj makes very explicit and Âchallenging use of her beauty and her body, so I thought of comparing her to some of the most famous courtesans in history: the Marquise de ÂMontespan, Comtesse du Barry, Madame de Pompadour, and ÂMadame Rimsky-ÂKorsakov. My idea was to reproduce four iconic portraits of some of the most fascinating females of the past in a series starring an American pop-culture role model. We tried to re-create those original portraits using similar furniture, props, and clothing, à la Visconti. Luckily enough, the result came out as surreal as it could be, just as I wished.BIESENBACH: Do you agree, as some of your critics suggest, that you’ve become too close to the leading powers in the art world?

VEZZOLI: The only power I have gotten too close to recently is the power to attract true stars to participate in my works—and, therefore, the challenge of dealing with them has become, for me, less engaging. I’ve worked with Lady Gaga, Cate Blanchett, Michelle Williams, Gore Vidal, and Natalie Portman, but I’m not interested in spending my time searching for the next big talent. That’s the mission of an agent.BIESENBACH: Years ago you were a challenging artist working in media and performance art. Your most recent show this past February, at Gagosian Gallery in New York, left many friends and critics angry and clueless. When you and I began discussing your upcoming touring retrospective around four years ago, the work felt as far away from the market and as impossible as one could imagine.

VEZZOLI: Yes, my most recent solo show at Gagosian left most of the critics angry and clueless—that’s true—but it’s better to be heavily criticized than to go unnoticed. Religion, motherhood, glamour, fame: I was going to touch some universal raw nerves with those themes, and I kind of expected such a reaction.BIESENBACH: Some critics argued that you had sold out to [Larry] Gagosian, the art world’s most powerful dealer.

VEZZOLI: Gagosian offered me this very flattering opportunity; I was aware of the risk, so I tried to conceive a commercial exhibition that would address the notion of power itself. Many people failed to see the irony or simply didn’t like it. What can I say? Of the 30 solo exhibitions I have had over my 12-year career, six have been commercial; the rest have been in museums and art foundations. The market has never been on my agenda whatsoever. But I don’t see anything wrong with artists who pursue the market or collaborate more with galleries than with museums. After all, some galleries these days have shows that are academically more credible than those found in some museums—and budgets that are more generous than those of the church in the 15th century. I don’t see why artists should shy away from all that.I’m not so greedy about money, but when it comes to press, I am a true media whore. My work has always involved getting public figures to participate in projects that would challenge audiences and their perception of them. I’ve also tried to get public or private institutions to question their own image: I turned the Guggenheim Museum in New York into a nightclub-theater; the Gagosian Gallery in Rome into a perfume store, and the one in New York into a church; and I turned a section of the 2005 Venice Biennale into a small-time porn movie theater.